Fundamentals of Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder is chronic and can affect daily life, including employment,1-3 relationships,3-6 and physical health.7-9 You can make a difference for your patients by providing access to adequate treatment, including pharmacotherapy10-12 and psychotherapy,13-15 and by helping them build a supportive personal and professional care network,16,17 giving them the tools to live fulfilling lives.18-20

Skip to section

Introduction to Bipolar Disorder

What Is Bipolar Disorder?

There is a lot of stigma and misunderstanding surrounding bipolar disorder, making it difficult for patients to accept it as a diagnosis and stick to treatment plans. Understanding what bipolar disorder is and options for management can help provide hope to patients. Bipolar disorder is a mood disorder characterized by alternating states of depression and mania or hypomania.21 People with bipolar disorder can also experience episodes of euthymia, during which they have few or no symptoms.22 Typically, depressive episodes last longer than mania or hypomania.23 Bipolar disorder shares characteristics with depressive disorders, schizophrenia, and other psychotic disorders.21

Manic Episode/Mania

A mood state that can include an abnormally elevated or irritable mood, hyperactivity, increased self-esteem, decreased need for sleep, racing thoughts, being more talkative than usual, and psychosis.21

Hypomanic Episode/Hypomania

A milder form of mania that can include abnormally elevated or irritable mood, increased self-esteem, decreased need for sleep, racing thoughts, and being more talkative than usual. Does not include psychosis.21,22

Depressive Episode/Depression

A mood state that can include depression, decreased energy, frequent hypersomnia or insomnia, and feelings of worthlessness or guilt.21

It is common for people with bipolar disorder to experience episodes that include symptoms of the opposite polarity – these are called episodes with mixed features.22,24,25 For more information on mixed features, scroll down to the Diagnosis section of this primer.

Types of Bipolar Disorder

The DSM-5 has 4 classifications for bipolar disorder.

Bipolar I

Characterized by both manic and depressive episodes.21,22

Bipolar II

Characterized by both hypomanic and depressive episodes.21,22

Cyclothymia

Related to bipolar disorder, it features both hypomanic and depressive symptoms that never meet the full criteria for diagnosis of hypomanic or depressive episodes.21 Individuals can also experience impulsive and anxious behaviors.26

Other Types of Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder may result from medications, substance use, or another medical disorder. Some individuals may show bipolar-like symptoms that do not fit the criteria for bipolar I, bipolar II, or cyclothymic disorder. These individuals may be given a diagnosis of other specified bipolar and related disorder.21

What Is the Burden of Bipolar Disorder?

Prevalence

In the US, 1.1% of adults aged 18 to 64 will be diagnosed with bipolar I disorder and 1.4% will be diagnosed with bipolar II disorder at some point in their lifetime27, with males and females being equally affected. It was estimated that in 2015 there were 2,477,737 adults in the US with bipolar I disorder.28 According to data from Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, in 2017, 567,216 adults in the US received a bipolar disorder diagnosis.29

Functional Impairment

Your patients with bipolar disorder may experience a decrease in quality of life and have difficulty performing regular tasks, having healthy relationships, and retaining employment,21,30 even during periods of euthymia.21,31 Beyond its effects on mood, people with bipolar disorder can experience cognitive impairment, and people with psychosis can experience a greater decline in cognitive function.31

Impairments in processing speed, working memory, and attention can lead to difficulties in thinking, focusing, and responding to what is happening around them.31 Your patients may also experience verbal and episodic memory deficiencies and not be able to easily remember words or details of specific events.31 Executive function, such as seeing tasks through from start to finish, may also be negatively impacted.31 People with bipolar disorder may also find it difficult to correctly read the emotions of other people.32

These effects of bipolar disorder can negatively impact relationships32 and may lead to unemployment.33 In 2002, individuals with bipolar disorder lost an average of 27.7 days of work due to absenteeism, and lost the equivalent of 35.3 workdays due to presenteeism (using DSM-IV criteria).34 In 2017, 17.9% of adults with bipolar disorder reported being unemployed.29 People with bipolar disorder may also experience stigma and exclusion in the workplace due to misconceptions about their condition, and this discrimination is associated with higher rates of unemployment.33

Bipolar disorder may impact more than your patient. Caring for a person with bipolar disorder can be time consuming and emotionally challenging. This can lead to financial, physical, and emotional hardships for family or other regular caregivers.28,35,36

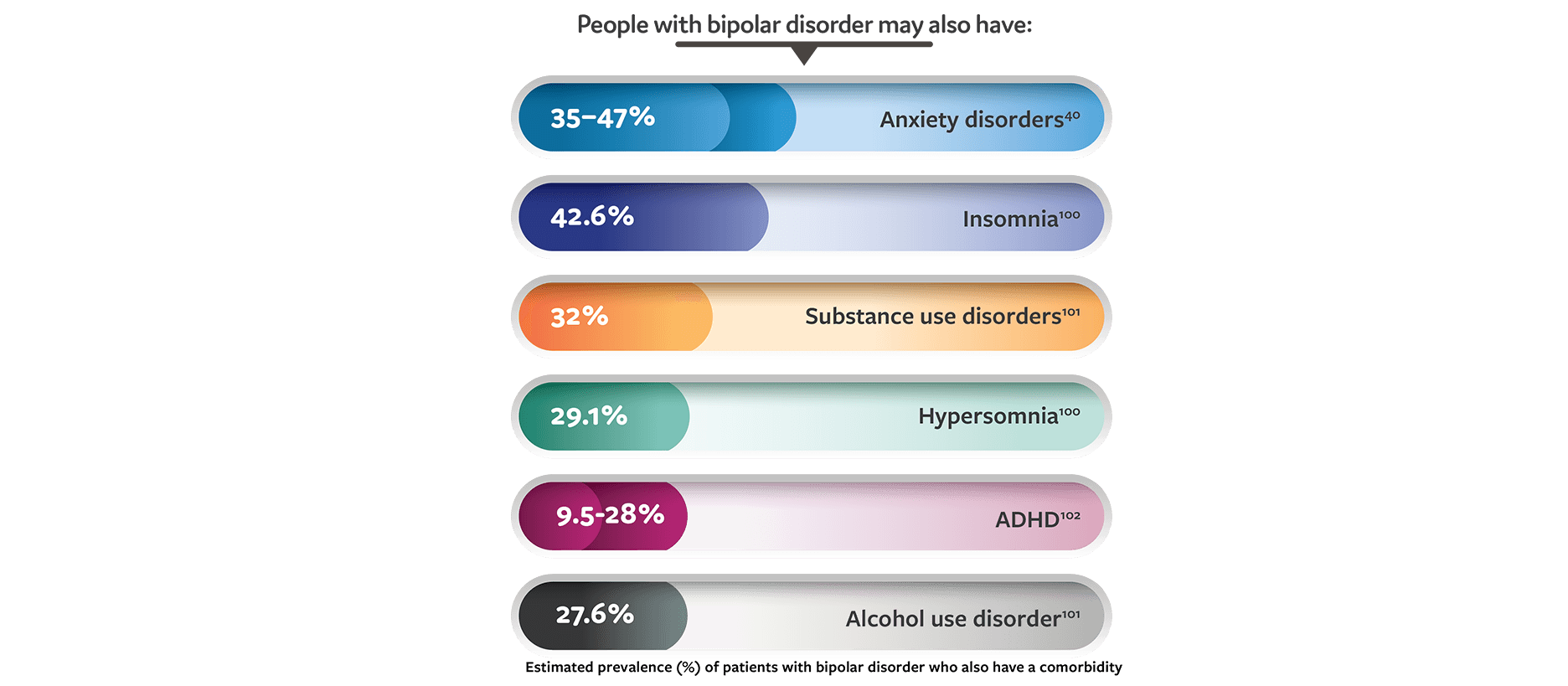

Comorbidities

Bipolar disorder is associated with many comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, asthma, migraine, and other psychiatric conditions, including substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, and personality disorders.37 Comorbid psychiatric disorders are associated with poor response to treatment and an increase in symptom severity.22,38-41

Substance use disorders, in particular, are strongly associated with bipolar disorder and can increase cognitive defects.42 They can also complicate treatment by increasing the severity of symptoms and decreasing access to care and treatment adherence.39

Rarely, some medical conditions can cause bipolar disorder, and bipolar disorder symptoms can worsen the original condition and impair treatment.21 While bipolar disorder symptoms may resolve with adequate management of the underlying disease (eg, Cushing’s disease),43,44 people with more permanent conditions (eg, brain injuries) may find it more difficult to manage the symptoms of bipolar disorder.21,45 Other medical conditions that have been found to cause symptoms of bipolar disorder include stroke,46 primary psychogenic polydipsia with associated hyponatremia,47 human immunodeficiency virus,48 and syphilis.49

Suicide Risk

People with bipolar disorder, especially those with predominant depressive episodes, are at a greater risk for suicide.50,51 A 2015 Centers for Disease Control survey of 27 states found that 15.2% of people who completed suicide had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.52 A large epidemiologic study found the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts is 20.9% for people with bipolar I disorder and 15.9% for bipolar II disorder,53 and another study found that about 7% will have suicidal ideation at least once in their lifetime.54

People with bipolar disorder may wait as long as 10 years to receive a correct diagnosis, and delays in receiving adequate treatment can lead to an increased number of suicide attempts and completions (Figure).55 Episodes with depressive features are more strongly associated with an increased number of suicide attempts in people with bipolar disorder.51 People who experience episodes with mixed features have a higher risk of attempting and completing suicide.51,53 It is uncommon for suicide attempts to occur during episodes of mania that do not have any mixed features.51 Because people with bipolar disorder have such an increased risk of suicide, frequently screening patients for potential symptoms is important.22,50 See the Diagnosis section below for more information on screening and assessment.

One study found that the longer a bipolar disorder went untreated, the greater the risk for suicide attempts. People with bipolar disorder who received adequate treatment in 2 years or less from the onset of symptoms had significantly fewer suicide attempts than those who waited longer than 2 years for adequate treatment.56

Pathophysiology of Bipolar Disorder

What Do We Know About the Causes?

While the causes of bipolar disorder are complex and not completely understood, being informed about its roots are important for diagnosis and treatment. Informing your patients about bipolar disorder can help them accept their diagnosis.57,58 When patients and their families have a better grasp of some of the environmental and social causes, they can better help develop, manage, and find success with their treatment plans.58,59 Scroll down to the Treatment Guidelines and Non-Pharmacological Management sections for more details on treatment options.

Research has shown that both genetic and environmental factors play a role. Bipolar disorder may be as much as 85% heritable, meaning that genetics can account for 85% of the differences in how bipolar disorder presents in different people.60,61 Close relatives of individuals who received a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder have an increased risk of developing the disorder.21,62 No specific genes passed from parent to child appear to be directly associated with bipolar disorder.63 Several genes have been associated with bipolar disorder, including those involved in calcium signal transmission, the glutamatergic system, and histone and immune pathways.64,65 However, more research is needed to understand the role that these pathways play in the development of bipolar disorders.22

While bipolar disorder has neurobiological underpinnings, the exact nature of those processes is not yet clear. Past research has focused on monoamine neurotransmitter systems, such as dopaminergic, serotonergic, and noradrenergic pathways, but so far no specific causal evidence has been found.22 The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis has also been researched, with similar results.12,66 More recently, the research focus has shifted to changes to brain synapses and neural plasticity.22 Some additional areas of neurobiological research include inflammation, the role of gut microbiota in inflammatory processes, mitochondrial dysfunction, microglial activation, and epigenetics.12,66-68

Many environmental factors have been associated with the development of bipolar disorders. Children exposed to prenatal maternal smoking and caesarean section delivery are at a higher risk of developing bipolar disorder later in life.69,70 Other risk factors implicated for bipolar disorder include advanced paternal age at conception and childhood trauma—including physical, sexual, and emotional abuse.71,72 Cannabis use during adolescence can lead to an earlier onset and increased severity of bipolar disorder, and treatment with some types of antidepressants can induce manic or hypomanic episodes.73-75 Other risk factors may include having an endocrine disorder, experiencing increased light exposure, or undergoing childbirth.7,76-78

Gene-environment interactions are likely a large contributor to the onset and development of bipolar disorder.22,79 While several pathophysiological associations and causes have been investigated, none have yet been identified as leading to bipolar disorder.22 Continuing research is focused on diagnostic criteria to improve early intervention and tailored treatment approaches to different bipolar disorder stages and presentations.22

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of bipolar disorder can be challenging. Typically, the disorder has a complex presentation and many of its symptoms overlap with other mental disorders.21,80 Some people with bipolar disorder may not receive an accurate diagnosis for as long as 10 years. This is particularly true for individuals whose first episode is of a depressive polarity.55,81 As most individuals with bipolar disorder have a first episode of depressive polarity,82-84 major depressive disorder is a frequent misdiagnosis.85,86 Because early intervention is an important factor in a good prognosis,22,55,87 a careful evaluation of the patient’s history and the use of validated screening tools is important, especially in primary care settings where providers may be less familiar with the early signs of bipolar disorder.80,86,88 Nurse practitioners (NPs) are likely to encounter and treat many patients who have bipolar disorder, making the NP’s role pivotal in these patients’ lives.80,87,89

The DSM-5 (2013) lists 3 distinct types of bipolar disorder:

- Bipolar I Disorder

When a person has at least 1 manic episode. They may also have hypomanic or depressive episodes, but those are not required for a diagnosis.21

- Bipolar II Disorder

When a person has at least 1 hypomanic and 1 major depressive episode. The presence of any full manic episodes indicates bipolar I disorder.21

- Cyclothymic Disorder

When a person has frequent periods of hypomanic and depressive symptoms that do not meet the criteria for hypomanic or major depressive episodes.21 Some people have a long-term cycling pattern between mood states, while others have more rapid fluctuations of mood that include impulsive and anxious behaviors.26 People who have been given a cyclothymic disorder diagnosis may develop bipolar I or II disorder.22,26

Bipolar disorder may be a secondary diagnosis or may present in a way that does not fit into the 3 above types:

- Substance/Medication-Induced Bipolar and Related Disorder or Bipolar Disorder Due to Another Medical Condition (sometimes referred to as "secondary mania" in the literature)

When bipolar-like symptoms are the result of some medications, some medical conditions, or substance intoxication or withdrawal. One important exception is antidepressant-induced mania or hypomania – this indicates a true bipolar disorder diagnosis.21

- Other Specified Bipolar and Related Disorder

When a person has symptoms of bipolar disorder that have a negative impact on their life, yet do not fit the criteria for bipolar I, II, or cyclothymic disorders.21

- Unspecified Bipolar and Related Disorder

Signs and symptoms

Talking to Your Patients

It can be difficult to translate a list of discrete, clinical symptoms to a diagnosis, especially for a sensitive topic such as bipolar disorder. A part of making an accurate diagnosis is asking the right questions.

Patients may not report symptoms of bipolar disorder, especially symptoms of hypomania or mania, if they do not perceive them to be a problem,88 or if they do not think of them as connected to a mental disorder.90 When assessing a patient, it is important for you to ask about specific symptoms in a way that is approachable. Some ways to do this are:

- Describe symptoms in a way that your patients can relate to in their day-to-day lives. Turning each symptom into a question38 and encouraging detailed responses may help with your patients’ understanding and lead to sharing symptoms they may not have otherwise noticed.90 For example, if asking about elevated self-esteem, one question could be, “Do you recall feeling more attractive than usual? Do you remember having a lot more sexual energy or interest than usual?”38

- Use the proper screening tools for bipolar disorder, especially when making a differential diagnosis.86,88

- Collect a thorough history, including any symptoms of hypomanic, manic, or depressive episodes in close family members.91 Because it takes most people with bipolar disorder anywhere from a year to a decade to get a correct diagnosis,91,92 try to get your patient to think about symptoms that may have happened further back than the last few months.

- Developing a strong relationship with your patient may help to lessen the stigma of a mental disorder diagnosis.93,94 It can also help reduce stress, encourage patients to be involved with their care plan and increase treatment adherence.91,93

- Avoid using jargon—using plain language and avoiding technical medical terms will improve your communication with your patient.95 Additionally, using proper terminology may help to lessen the stigma of a mental disorder diagnosis96,97—for example, the term manic-depressive is outdated and associated with a person with severe psychosis.88

Using these methods to communicate the symptoms listed here can be helpful for patient communication and making a diagnosis.

Symptoms of a Manic Episode21

According to the DSM-5 criteria, a manic episode is when a person is in an unusually energetic, effusive, or irritable mood that lasts a week or longer. To qualify as a manic episode, the mood must be sufficiently severe to cause marked functional impairment, have features of psychosis, or require hospitalization. This mood is accompanied by several additional symptomsa:

- Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

- Decreased need for sleep

- More talkative than usual

- Racing thoughts

- Distractibility

- Increased activity or psychomotor agitation

- High-risk behavior with potential serious consequences (ie, a shopping spree or sexual indiscretion)

- Resisting treatment

- Changes in dress and appearance to attract more attention

- Perceived increase in sensory sensitivity

- Aggression and hostile behavior

- Rapid mood changes

- Depressive symptoms (mixed symptoms)

- Psychotic features

- Delusions

- Hallucinations

- Confusion

- Violence

- Regression or catatonia

- Fecal incontinence

Symptoms of Hypomania21

According to the DSM-5 criteria, a hypomanic episode is when a person is in an unusually energetic, effusive, or irritable mood that lasts at least 4 days. This mood is accompanied by several additional symptomsa:

- Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

- Decreased need for sleep

- More talkative than usual

- Racing thoughts

- Distractibility

- Increased activity or psychomotor agitation

- High-risk behavior with potential serious consequences (ie, a shopping spree or sexual indiscretion)

- Impulsivity

- Increased creativity

Symptoms of Major Depression21

According to the DSM-5 criteria, a person is experiencing a depressive episode when there is a noticeably depressed mood or loss of interest and pleasure in most activities for at least 2 weeks. This mood is accompanied by several additional symptomsa:

- Depressed mood for most of each day

- Loss of interest or pleasure in most activities

- Decrease or increase in appetite, or a ≥ 5% unintentional increase or decrease in weight in a 1-month period

- Insomnia or hypersomnia

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation observable by others

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness, or excessive or inappropriate guilt

- Inability to think, concentrate, or make decisions

- Recurrent thoughts of death, recurrent suicidal ideation, having a specific plan for suicide, or a suicide attempt

In addition to the above lists, during an acute depressive episode the following symptoms may be present92:

- Delusions

- Hallucinations

- Loss of libido

- Physical ailments

Specifiers

Specifiers are descriptors in the DSM-5 that can be added to a diagnosis of bipolar and related disorders, allowing for the description of additional symptomsa or patterns that are not part of the base diagnosis.22 A patient that has a specifier as a part of their diagnosis is not unusual – rather, the specifiers allow for a more nuanced diagnosis and treatment plan.

aThe symptoms in these definitions are adapted from the DSM-5 (2013) so as to avoid any misinterpretation. Please refer to the DSM-5 (2013) published by the American Psychiatric Association for the full diagnostic criteria.

Specifier21 | Definition | Can be applied to… |

| Anxious distress | The presence of at least 2 of the following symptoms for most days of an episode:

| The most recent or current manic, hypomanic, or depressive episode in bipolar I or bipolar II disorder |

| Atypical features | The presence of mood reactivity, when the mood brightens in response to actual or potential positive events, along with at least 2 of the following symptoms:

| The most recent or current episode of depression in bipolar I or bipolar II disorder |

| Catatonia | Three or more of the following symptoms are present:

| Manic or depressive episode in bipolar I or bipolar II disorder |

| Melancholic features | When the person experiences loss of pleasure in activities or lack of reactivity to pleasurable stimuli, along with at least 3 of the following symptoms:

| During the most severe period of the most recent or current depressive episode in bipolar I or bipolar II disorder |

| Mixed features | If experiencing a hypomanic or manic episode, at least 3 of the following depressive symptoms are also present:

| The most recent or current manic, hypomanic, or depressive episode in bipolar I or bipolar II disorder |

| Peripartum onset | The onset of the mood episode happens during pregnancy or in the 4 weeks postdelivery. | The most recent or current manic, hypomanic, or depressive episode in bipolar I or bipolar II disorder |

| Psychotic features | The presence of delusions or hallucinations during an episode. | Manic episodes in bipolar I or bipolar II disorder |

| Rapid cycling | Presence of at least 4 mood episodes in the past 12 months, separated by partial or full remission for at least 2 months, or by a switch to the opposite mood polarity. | Bipolar I or bipolar II disorder |

| Seasonal pattern | A long-term pattern of at least 1 type of mood episode occurs and then subsides or changes corresponding with a particular time of year. This must happen for at least 2 years, with no nonseasonal episodes occurring during that same period. | Manic, hypomanic, or depressive episodes in bipolar I or bipolar II disorder |

Diagnostic and Screening Tools

There are a number of validated scales you can use to assess symptoms related to bipolar disorder. While these scales are useful tools, it is important to make a careful assessment of the whole patient prior to making a diagnosis.38,80 A selection of diagnostic and screening tools can be found here.

For additional information about the diagnosis process, scroll down to the Treatment Guidelines section.

Potential Differential Diagnoses

Bipolar disorder has symptoms that overlap with other mental disorders, and can also be comorbid with many of those disorders, making it difficult to diagnose.21,91 For example, symptoms of some disorders, such as borderline personality disorder and impulse-control disorders, are associated with a misdiagnosis,98 but bipolar disorder can also be comorbid with impulse-control disorders.21 This makes a careful evaluation of patient symptoms and history important for proper treatment. Other diagnoses that should be considered prior to making a diagnosis of bipolar I or II disorder include21:

- Major depressive disorder: While both disorders involve depressive episodes, major depressive disorder can be distinguished from bipolar disorder by screening for a history of hypomanic or manic episodes.38,91

- Other types of bipolar disorder, including another medical condition, substance, or medication-induced bipolar disorder: Examining the timing of bipolar-like symptoms with medical conditions or use of substances or medications can help make an accurate diagnosis. Cyclothymic disorder can be distinguished if the hypomanic or depressive symptoms are not sufficient to be counted as a full episode.91

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): ADHD and bipolar disorder share many symptoms, including emotional lability, impulsivity, and restlessness.99 Interviewing for ADHD-specific symptoms, such as inattention, can help make a diagnosis.99 In addition, bipolar disorder is episodic, whereas ADHD is ongoing and typically does not include decreased need for sleep, hypersexuality, psychotic symptoms, or suicidal thoughts.91

- Personality disorders: While symptoms such as impulsivity, lack of empathy, grandiosity, or not respecting boundaries can be similar between personality disorders and bipolar disorder, these symptoms happening outside of a manic episode can indicate a personality disorder. Family history, symptom onset, and additional symptoms can also help distinguish a personality disorder from bipolar disorder.91

- Disorders in which severe irritability is a symptom, if manic or hypomanic episodes are not sufficiently distinct.21

Other diagnoses that should be considered prior to making a diagnosis of cyclothymic disorder include21:

- Other types of bipolar disorder with rapid cycling

- Bipolar or depressive disorder due to a medical condition or induced by a substance or medication: Cyclothymic disorder can be distinguished from bipolar disorder if the hypomanic or depressive symptoms are not sufficient to be counted as a full episode.91

- Borderline personality disorder: While manic symptoms can be similar to those of borderline personality disorder, unstable relationships with others, fluctuations in mood and self-image, and fear of abandonment can distinguish this diagnosis from cyclothymic disorder.91

Other diagnoses that should be considered prior to making a diagnosis of bipolar and related disorder due to another medical condition include21:

- Delirium, catatonia, or acute anxiety caused by other disorders or medical conditions

- Depressive or manic symptoms as a result of medication use: Examining the timing of bipolar-like symptoms with use or discontinuation of substances or medications can help distinguish this diagnosis.21,91

Medical conditions that have been associated with bipolar disorder symptoms include:

- Cushing’s disease43,44

- Brain injuries21,45

- Stroke46

- Primary psychogenic polydipsia with associated hyponatremia47

- Human immunodeficiency virus48

- Syphilis49

Psychiatric Comorbidities

Bipolar disorder can also be comorbid with other mental and medical conditions many of which can have similar symptoms.80 It is important that patients receive accurate diagnoses so that they can receive an appropriate treatment option.

While it can be difficult and take time to diagnose a bipolar disorder, your patients will benefit from your persistence, care, and consideration.

Treatment Guidelines

Adequate management of bipolar disorder is important for your patients’ health and well-being.100 A longer period of untreated illness is associated with a worse overall prognosis, including an increased risk of suicide and longer lengths of episodes.22,101-103 There is some evidence that early intervention may improve prognosis and is dependent on timely diagnosis and treatment. However, the staged treatment model—treating mental disorders differently based on how much the disorder has progressed—is still new, and more research is needed to understand how it can be used to benefit patients with bipolar disorder.22,100

The treatment guidelines listed below were selected using an objective and systematic, but not exhaustive, process (see below for the methodology used). These guidelines are for educational use only. Abbvie Inc was not involved in the development of the guidelines listed below and does not endorse the use of any specific guidelines. As NP Psych Navigator is a resource for US healthcare providers, we have only included guidelines from US-based organizations. They are provided here for your convenience in alphabetical order. Healthcare providers should use their clinical judgement to determine which guidelines are appropriate for use in their clinical practice.

Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder104

- Supporting Organization: American Psychiatric Association

- Published: 2002

- Description: These guidelines were based on a comprehensive literature review and clinical consensus from a working group of clinical and research psychiatrists. Guidelines were targeted towards patients who are older than 18 years, used criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) and pertained to the treatment of bipolar I and II disorders. Treatment guidance was for both acute and maintenance treatment, and included the treatment of manic episodes, mixed episodes, depressive episodes, rapid cycling (considered a separate diagnosis in the DSM-IV), patient and family education, treatment adherence, functional impairment, and lifestyle changes. The guidelines also included information on clinical features that may affect treatment, including gender, pregnancy, age, and psychiatric and physical comorbidities.

- Grading: Evidence was evaluated by clinical consensus. Recommendations were categorized from level 1 (substantial clinical confidence) to level 3 (may be useful for individual circumstances).

Methodology for Guideline Selection

On April 16, 2020, the following search string was entered into the PubMed database:

(bipolar[Title/Abstract]) AND (treatment[Title/Abstract]) AND (guideline*[Title] OR guidance[Title]). The search was limited to PubMed, the most commonly used medical publications database in the world, to ensure that this list can be consistently maintained and updated.

Results were restricted to those publications from the year 2000 to the date of the search, those published in English, and those indexed as article type, “Practice Guideline.” This search returned 26 results. These results were screened in depth according to the following exclusion criteria: articles that were not guidelines for clinical practice, such as research or study results, guidelines that had a published update (ie, only the most recent version of a set of guidelines were included), guidelines from any entity other than an established, professional clinical organization or a group of said organizations, guidelines from any non-US organization, guidelines that did not report their process for grading and evaluating recommendations, guidelines written for the use of a specific pharmacological or nutraceutical treatment, guidelines that are not available for free, guidelines for bipolar disorders secondary to another condition, and guidelines for conditions other than bipolar disorder.

Non-Pharmacological Management for Bipolar Disorder

For many of your patients, bipolar disorder episodes can be distressing.58 They can disrupt education,59 job paths,33 financial stability,21 relationships,32 and dreams for the future.105 But maintaining wellness can be equally as difficult.106

You may even hear your patients describe wellness as requiring concerted effort58,106—a balancing act of establishing routines,107 prioritizing their health,108,109 getting enough sleep,110 and regularly taking medications.57 This illness is incurable but can be manageable for many patients. When used with pharmacotherapy, nonpharmacological management such as psychotherapy and lifestyle changes can help patients feel more in control of their symptoms.111,112

What Are the Benefits of Psychotherapy?

Research shows that other types of treatments can be beneficial in addition to medication.22 Psychotherapists and peer-support groups can help patients better understand their condition, and reshape adverse thoughts or behaviors.111 Types of psychotherapy that have helped people with bipolar disorder are:- May reduce relapse rates, especially for people with bipolar I disorder.13,113,114 It may also help reduce the frequency and severity of depressive and manic symptoms115 and improve relationships and lifestyle satisfaction.116

- May improve emotional regulation for people with bipolar disorder and may reduce depressive and manic symptoms.117-119

- May reduce both depressive and hypomanic symptoms.120 It may also help prevent the onset of new episodes.121

Which Lifestyle Modifications Help With Bipolar Disorder?

There is no cure for bipolar disorder, but it is treatable.22 Recovery is not an endpoint, but a continuous process that focuses on resilience and staying in control.105 While return to premorbid functioning is not attainable for many patients, investment in actions that boost health and energy, continuing to take medications as prescribed, finding meaning in life, and making life changes can help them lead full lives.22,105,122 Discussing these changes with your patients can help them make the right choices for their needs.

Education

Teaching patients about their medications, including potential interactions with other medications, has been shown to improve treatment adherence and quality of life.111,123

Substance Use

Limiting alcohol consumption has been shown to reduce the number of manic and depressive episodes.124 Avoiding caffeine and other mood-altering substances can also be beneficial.111

Healthy Diet

Having a well-balanced diet with more whole foods and limiting sugar intake can reduce the number of manic and depressive episodes.111,124,125

Sleep Hygiene

Developing good sleep hygiene, especially a regular schedule, can reduce mania and is thought to reduce the progression of bipolar disorder.111,126-128

Exercise

Performing regular exercise may reduce mood symptoms. Aerobic exercise is thought to be especially beneficial.111,125,129

Routines

Keeping to a regular schedule helps to create structure, manage potential stressors, and reduce episode recurrence.111,121 Investing in volunteering or a hobby can be helpful in maintaining a schedule, especially if paid employment is not possible.111

How Can Patients Plan?

Patients integrate their bipolar disorder diagnosis into their lives and identities in different ways.58 Some share their diagnosis with friends and family to build support networks, while others worry about stigma and prefer to manage their moods privately.130 Regardless of approach, proper planning can help mitigate the more difficult aspects of the illness, such as when a depressive episode leads to suicidal ideation or mania leads to spending sprees.111

Prevention and management tactics can help patients feel better equipped to cope with bipolar disorder.111 Identifying and controlling stressors, symptoms, and crisis situations can also help patients with bipolar disorder management.111 You can help your patients plan:

Symptom Tracking

Tracking symptoms, stressors, and treatment effects can help. Identify triggers, indicators of developing symptoms, and methods to reduce and control symptoms. Mood and life charting can also help prevent recurrence.111,131 Some evidence suggests frequent use of validated mood evaluation scales can help with early detection of episodes.132

Family and Friends

Having a supportive social network of trusted people who have learned about bipolar disorder is associated with fewer total episodes and hospitalizations.1111,133

Budgeting

Using budget calculators and online tools such as automatic bill payments and spending notifications can help patients stay on top of their finances. Patients may also find it helpful to have trusted friends or family help monitor spending through formal (eg, power of attorney) and informal methods.134

Planning for the Future

Patients can ease stress and worry about a potential crisis by having an emergency plan. Relapse prevention and crisis plans can reduce both voluntary and compulsory hospitalization.135 Suggest that your patients make a short list to keep in a wallet or on a phone that contains contact information for the patient’s support network (doctors, nurse practitioners, family members, etc.).111 A plan may also include having a list of crisis hotlines and emergency walk-in centers for mental health.111

References

Goldberg, JF & Harrow, M. J Affect Disord. 2004;81(2):123-131.

Hakulinen, C et al. Depress Anxiety. 2019;36(11):1080-1088.

Kogan, JN et al. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(6):460-469.

Belardinelli, C et al. J Affect Disord. 2008;107(1-3):299-305.

Eidelman, P et al. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(6):628-640.

Goldstein, TR et al. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1-3):174-183.

Amann, BL et al. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(3):225-234.

Crump, C et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(9):931-939.

Vancampfort, D et al. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:219-224.

Miura, T et al. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(5):351-359

Tamayo, JM et al. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13(6):813-832.

Vieta, E et al. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14(8):1029-1049.

Chiang, KJ et al. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0176849.

Oud, M et al. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(3):213-222.

Scott, J et al. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;10(1):123-129.

Dunne, L et al. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2019;42(1):100-103.

Hendryx, M et al. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2009;36(3):320-329.

Crowe, M & Inder, M. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2018;25(4):236-244.

Russell, SJ & Browne, JL. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(3):187-193.

Sylvia, LG et al. J Affect Disord. 2014;169:144-148.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edn (2014).

Vieta, E et al. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18008.

Tondo, L et al. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(3):353-358.

McIntyre, RS et al. J Affect Disord. 2015;172:259-264.

Sole, E et al. CNS Spectr. 2017;22(2):134-140.

Perugi, G et al. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(3):372-379.

Kessler, RC et al. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21(3):169-184.

Cloutier, M et al. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:45-51.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, CfBHSaQ. Mental Health Annual Report: 2017. Use of Mental Health Services: National Client-Level Data. 2019. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Rockville, MD.

Oldis, M et al. J Affect Disord. 2016;195:148-155.

Bortolato, B et al. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:3111-3125.

Vaskinn, A et al. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2017;5(1):13.

O'Donnell, L et al. J Soc Social Work Res. 2017;8(3):379-398.

Kessler, RC et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1561-1568.

Blanthorn-Hazell, S et al. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2018;17:8.

Siddiqui, S & Khalid, J. Pak J Med Sci. 2019;35(5):1329-1333.

Patel, RS et al. Brain Sci. 2018;8(9).

Bobo, WV. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(10):1532-1551.

Salloum, IM & Brown, ES. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43(4):366-376.

Spoorthy, MS et al. World J Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):7-29.

Eisner, LR et al. J Affect Disord. 2017;220:102-107.

Cardoso, TA et al. Psychiatry Res. 2016;243:225-231.

Tsai, WT et al. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;70(1):71.

Ummar, IS et al. Indian J Psychiatry. 2015;57(2):200-202.

Perry, DC et al. J Neurosurg. 2016;124(2):511-526.

Santos, CO et al. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32(1):11-21.

Parag, S & Espiridion, ED. Cureus. 2018;10(11):e3645.

Nakimuli-Mpungu, E et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(8):1349-1354; quiz 1480.

Seo, EH et al. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2018;17:24.

Boggs, JM et al. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(6):677-684.

Schaffer, A et al. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49(11):1006-1020.

Stone, DM et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(22):617-624.

Baldessarini, RJ et al. Br J Psychiatry. 2019:1-6.

de Beurs, D et al. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):345.

Cha, B et al. Psychiatry Investig. 2009;6(2):96-101.

Altamura, AC et al. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;260(5):385-391.

Delmas, K et al. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199(2):136-139.

Proudfoot, JG et al. Health Expect. 2009;12(2):120-129.

Leahy, RL. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(5):417-424.

Edvardsen, J et al. J Affect Disord. 2008;106(3):229-240.

McGuffin, P et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(5):497-502.

Mortensen, PB et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(12):1209-1215.

Harrison, PJ et al. Trends Neurosci. 2018;41(1):18-30.

Network Pathway Analysis Subgroup of Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(2):199-209.

Nurnberger, JI, Jr. et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(6):657-664.

Muneer, A. Chonnam Med J. 2016;52(1):18-37.

Kato, T. Schizophr Res. 2017;187:62-66.

Pinto, JV et al. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16(5):519-532.

Chudal, R et al. J Affect Disord. 2014;155:75-80.

Talati, A et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(10):1178-1185.

Frans, EM et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(9):1034-1040.

Larsson, S et al. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:97.

Lagerberg, TV et al. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;261(6):397-405.

Lev-Ran, S et al. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209(3):459-465.

Viktorin, A et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(10):1067-1073.

Bauer, M et al. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(6):571-582.

Di Florio, A et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(2):168-175.

Wesseloo, R et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(2):117-127.

Misiak, B et al. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(6):5075-5100.

Scrandis, DA. Nurse Pract. 2014;39(10):30-37; quiz 37-38.

81 Fritz, K et al. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(5):396-400.

Forty, L et al. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(1):82-88.

Volkert, J et al. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:322.

Baldessarini, RJ et al. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;129(5):383-392.

Hughes, T et al. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(643):e71-77.

Kriebel-Gasparro, AM. Open Nurs J. 2016;10:59-72.

McCormick, U et al. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;27(9):530-542.

Koirala, P & Anand, A. Cleve Clin J Med. 2018;85(8):601-608.

Theophilos, T et al. Healthcare (Basel). 2015;3(1):162-171.

Regeer, EJ et al. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):22.

Yatham, LN et al. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

Fountoulakis, KN et al. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20(2):98-120.

Dang, BN et al. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):32.

Mestdagh, A & Hansen, B. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(1):79-87.

Hersh, L et al. Am Fam Physician. 2015;92(2):118-124.

Broyles, LM et al. Subst Abus. 2014;35(3):217-221.

Thom, RP & Farrell, HM. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(3):253-259.

Zimmerman, M et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(1):26-31.

Kitsune, GL et al. J Affect Disord. 2016;192:125-133.

Rios, AC et al. Braz J Psychiatry. 2015;37(4):343-349.

Dome, P et al. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(8).

Medeiros, GC et al. Braz J Psychiatry. 2016;38(1):6-10.

Zhang, L et al. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44811.

American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(4 Suppl):1-50.

Jacob, KS. Indian J Psychol Med. 2015;37(2):117-119.

Maassen, EF et al. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6(1):23.

National Alliance on Mental Illness. Bipolar Disorder: Support. Mental Health Conditions. 2020. https://www.nami.org/learn-more/mental-health-conditions/bipolar-disorder/support. Accessed April 1, 2020.

Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance. Exercise. DBSA Wellness Toolbox: Lifestyle. 2020. https://www.dbsalliance.org/wellness/wellness-toolbox/lifestyle/exercise/.

Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance. Nutrition. DBSA Wellness Toolbox: Lifestyle. 2020. https://www.dbsalliance.org/wellness/wellness-toolbox/lifestyle/nutrition/. Accessed April 1, 2020.

Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance. Sleep. DBSA Wellness Toolbox: Lifestyle. 2020. https://www.dbsalliance.org/wellness/wellness-toolbox/lifestyle/sleep/. Accessed April 1, 2020.

Duckworth, K. Understanding Bipolar Disorder and Recovery. (National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2008).

Health, NIoM. Bipolar Disorder. 2018. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Bethesda, MD. 9-MH-8088.

Jones, SH et al. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;206(1):58-66.

Lam, DH et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):145-152.

Costa, RT et al. Braz J Psychiatry. 2011;33(2):144-149.

Miklowitz, DJ et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(9):1340-1347.

Eisner, L et al. Behav Ther. 2017;48(4):557-566.

Goldstein, TR et al. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25(2):140-149.

Zargar, F et al. Adv Biomed Res. 2019;8:59.

Swartz, HA et al. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(2):211-216.

Frank, E et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(9):996-1004.

Parekh, R. What are Bipolar Disorders? American Psychiatric Association Website. . 2017. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/bipolar-disorders/what-are-bipolar-disorders. Accessed April 10, 2020.

Mishra, A et al. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:722.

Huang, J et al. Psychiatry Res. 2018;266:97-102.

Sylvia, LG et al. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2013;1(1):24.

Harvey, AG et al. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(3):564-577.

Steardo, L, Jr. et al. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:501.

Steinan, MK et al. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;133(5):368-377.

Ng, F et al. J Affect Disord. 2007;101(1-3):259-262.

Cross, W & Walsh, K. Star Shots: Stigma, self disclosure, and celebrity in Bipolar Disorder. in Bipolar Disorder - A Portrait of a Complex Mood Disorder (ed J Barnhill) 221-236 (In Tech, 2012).

Yasui-Furukori, N & Nakamura, K. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:733-736.

Vazquez-Montes, M et al. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6(1):7.

Cohen, AN et al. J Affect Disord. 2004;82(1):143-147.

Bond, N & Clark, T. (ed Money and Mental Health Policy Institute) (London, UK, 2019)

Murton, C et al. Psychiatr Bull (2014). 2014;38(6):276-280.

This resource is intended for educational purposes only and is intended for US healthcare professionals. Healthcare professionals should use independent medical judgment. All decisions regarding patient care must be handled by a healthcare professional and be made based on the unique needs of each patient.

ABBV-US-00433-MC

Approved 01/2024

AbbVie Medical Affairs

Additional Resources about Bipolar Disorder

Clinical Article

Unrecognized Bipolar Disorder in Patients With Depression Managed in Primary Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Daveney et al explore the characteristics of patients with mixed symptoms, as compared to those without mixed symptoms, in both bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder.