Fundamentals of Major Depressive Disorder

Patients with major depressive disorder experience episodes of sadness or feelings of worthlessness that can make routine tasks such as working,1,2 caring for others, 3,4 sleeping,5 eating well,6-8 and exercising 9,10 seem insurmountable. Proper care, including pharmacotherapy,11 psychotherapy,12,13 and the support of family and friends,14-16 creates a recovery support system, helping individuals become more resilient and live independent fulfilling lives once again.17-19

Skip to section

Introduction to Major Depressive Disorder

What Is Major Depressive Disorder?

There is a lot of stigma surrounding depressive disorders, making it difficult for patients to be open about their diagnosis and seek treatment. Understanding their depressive symptoms and options for management can help provide hope to patients. Depressive disorders are typically characterized by feelings of sadness, depression, or irritability.20 While the various depressive disorders share common symptoms, the specific types are differentiated by the timing and length of the symptoms.20 Major depressive disorder is the most recognized disorder in this group. People with major depressive disorder experience prolonged depressive episodes that involve changes in mood, cognition, and a loss of interest and pleasure in previously-enjoyed activities.20

Types of Depressive Disorders

The DSM-5 (2013) describes 3 depressive disorders that affect adults.

Major Depressive Disorder

Characterized by a depressed mood for at least 2 weeks20

Persistent Depressive Disorder

Characterized by a depressed mood for most days for 2 years20

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

Marked depressed mood or irritability develop during the week before menses. These symptoms are minimal or absent once monthly menses is complete20

Depressive disorders may be secondary to another process or may present differently than the types listed above.

- The use of mind-altering substances, some medications, and some medical conditions can cause depressive-like symptoms. In these cases, a diagnosis of substance/medication-induced depressive disorder or depressive disorder due to another medical condition may be given.20

- A patient with depressive symptoms that do not fit the criteria for any of the above disorders may be classified as having other specified depressive disorder.20

- Sometimes when no specific diagnosis can be made, such as in an emergency department in which pertinent medical information is unavailable, a diagnosis of unspecified depressive disorder may be rendered.20

What Is the Burden of Major Depressive Disorder?

Prevalence

Depressive disorders are the leading cause of disability in adults worldwide.21

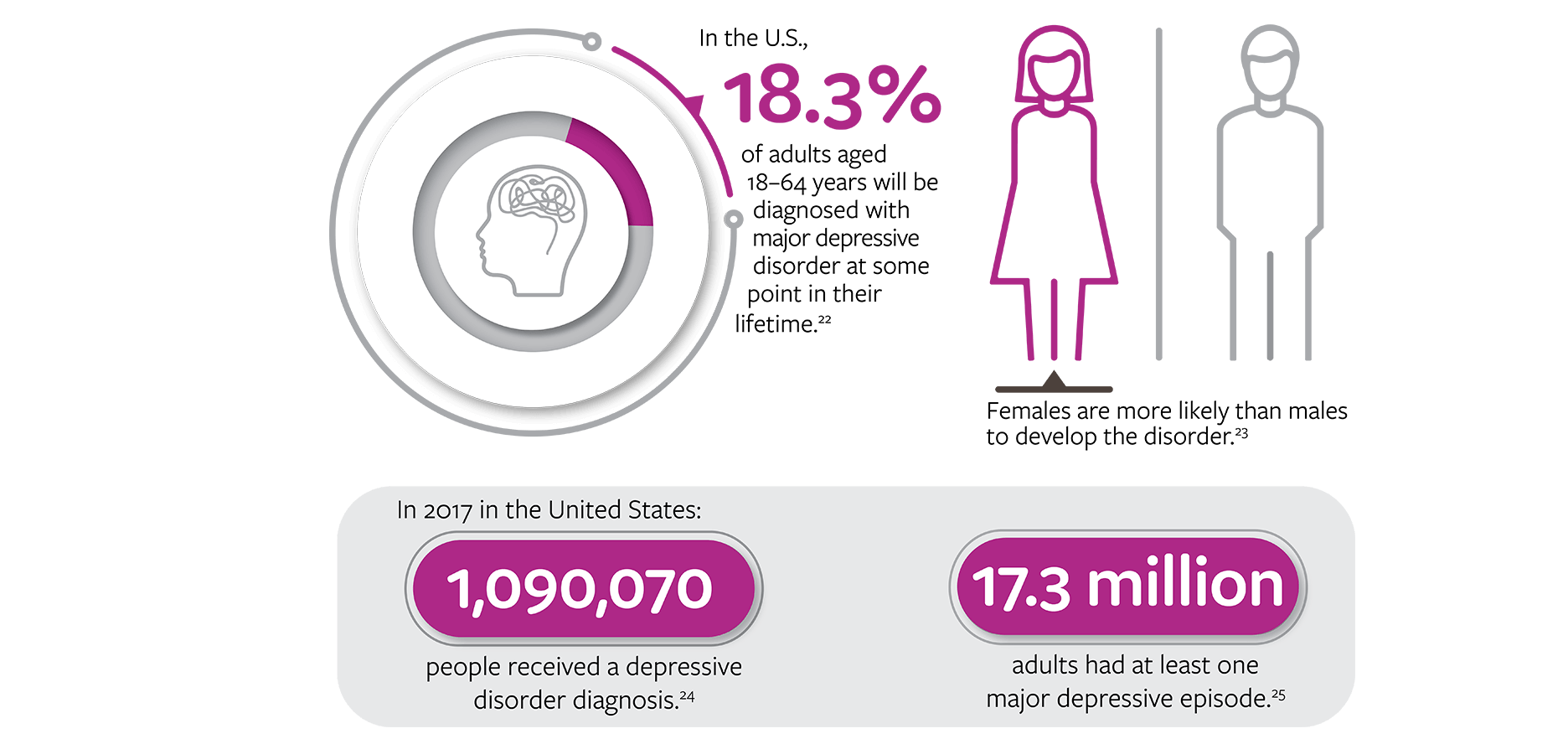

In the US, 18.3% of adults aged 18–64 years will be given a diagnosis of major depressive disorder at some point in their lifetime. Females are more likely than males to develop the disorder. In 2017, 1,090,070 people in the US received a depressive disorder diagnosis and 17.3 million adults had at least 1 major depressive episode. [22-25]

Functional Impairment

Major depressive disorder can reduce your patients’ quality of life and may make performing day-to-day functions difficult.26 Depressive episodes can affect memory, attention span, conversational skills, and executive functioning, which involves decision making and task completion.23,26,27 These difficulties can persist outside depressive episodes.23,26 Research has shown that higher levels of education can confer protection against depressive symptoms.28

Relationships with coworkers, friends, and acquaintances may also be affected by depressive symptoms. People with major depressive disorder can miss work due to their illness and, when at work, may perform responsibilities poorly or ineffectively due to their condition.26 In a survey from 2001–2003, people with major depressive disorder lost an average of 27.2 workdays—8.7 days were due to absenteeism and 18.2 days from presenteeism.29 Problems with memory, attention, and executive function are also associated with lower wages and unemployment.26,28 Patients with major depressive disorder may have difficulty extricating themselves from their own thoughts and, as a result, may appear self-focused and disinterested in social activities and forging bonds with others.30 Along with a diminished ability to read nonverbal cues from other people, they may come across as insensitive and have few friends.30

Caregivers such as family and friends of people with major depressive disorder can also be negatively impacted. This unpaid informal work can be time consuming and emotionally challenging,31 possibly leading to lost income and health insurance due to reduced work hours.32 In addition, they may experience fatigue, distress, and poor sleep, and may develop depressive symptoms themselves.32

Comorbidities

People with major depressive disorder are at an increased risk for developing cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, obesity, metabolic syndrome, epilepsy, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, and cancer.23,33 Some of these conditions, such as obesity34 and cardiovascular disease,35,36 have also been linked to the development of major depressive disorder. Insomnia is also associated with an increased risk for developing major depressive disorder.37 Comorbidities can make it more difficult to adequately treat major depressive disorder and can increase cognitive dysfunction.23,38

Suicide Risk

Suicide is a significant concern; people with major depressive disorder have an almost 20-times greater risk of attempting suicide than the general population, more than half will have suicidal ideation at least once in their lifetime, and 31% will attempt suicide.23,39,40

A US survey from 2012–2013 found that 305 adults (of more than 30,000 surveyed) had attempted suicide in the last 3 years. Of those who attempted suicide, 54% had major depressive disorder in the year prior to the survey.41 The presence of mixed features (manic symptoms) during a depressive episode increases the risk of suicide.42 Because of the high risk of suicide, screening your patients regularly for suicidal thoughts or intent is important. See ‘Diagnosis’ below for more information on screening and assessment.

Pathophysiology of Major Depressive Disorder

What Do We Know About the Causes?

Misperceptions about major depressive disorder persist despite the body of research suggesting the disorder is as real and concrete as the common cold.43,44 This lingering stigma may lead some patients and their families to underestimate the severity or significance of major depressive disorder symptoms.45,46 Instead, they may blame external causes such as stress or relationship problems rather than considering biologically based factors.47,48 Such misunderstanding can hinder recovery by inadvertently causing delays in seeking treatment for symptoms,45 and when these patients do reach out, they may not adhere to treatment as prescribed or recommended.43,49 When you educate your patients about major depressive disorder being a medical condition that has biological and environmental causes, you can empower them to become an active part of their treatment plan and recovery.43 Scroll down to the Treatment Guidelines and Non-Pharmacological Management sections for more details on treatment plans.

Genetic

Although researchers have not found any single mechanism known to cause major depressive disorder, they are aware that it may have a genetic component.23,50-57 Genetics cause 28% to 44% of the variation observed in how major depressive disorder presents.50,52,54 First-degree relatives of people who have major depressive disorder have an almost 3-fold risk of developing it.57 Many genes contribute to the condition, including some related to neuroticism, which has been linked in the development of major depressive disorder.51,53,55,56 Identifying candidate genes is difficult, because many are likely to confer higher risk only when combined with specific environmental stressors.23

Neurobiological

Multiple neurobiological processes are thought to contribute to major depressive disorder. The brains of people who have this condition have been shown to have lower cortical thickness and cell density in the prefrontal cortex, reduced hippocampus volume, and changes to synapse structure and function.58

Several biomarkers have been identified as related to synapse function.58 Two of these biomarkers, brain-derived neurotrophic factor and protein p11, have been identified as potential biomarkers for predicting antidepressant response and risk of suicidality, respectively.58 Epigenetics are also thought to play a role in synapse plasticity.58 Antidepressants, exercise, and electroconvulsive therapy have been shown to promote increased hippocampus volume and neuroplasticity.59,60

Environment

Stressful events, including job strain, loss of employment, financial insecurity, health problems, exposure to violence, separation from a partner or family, and grieving the loss of a loved one, can initiate a depressive episode.61-64

Increased levels of cortisol, a glucocorticoid hormone associated with acute and chronic stress, are a risk factor for major depressive disorder.65-67 Using synthetic glucocorticoids for the management of other medical disorders, such as autoimmune diseases and asthma, can increase the risk of major depressive disorder and suicide.68,69 For some people who have major depressive disorder, an overactive peripheral immune system can lead to high levels of proinflammatory cytokines.58 Some research shows that maternal stress in utero may be connected with the development of depressive symptoms when the children become adolescents.70,71 The stress of pregnancy and birth leads to major depressive disorder for 6% to 8% of women annually in the US.72

Prevention and Future Research

While some causes cannot be avoided, there are steps that can be taken to reduce the risk for developing major depressive disorder. Prevention tactics can include the patient learning how to strengthen social networks and problem-solving skills, and proactively treating depressive symptoms before they develop into major depressive disorder.

Taking these steps and others can lead to an average of a 21% reduction in the incidence of major depressive disorder.73 For people with high inflammatory biomarkers, treating the inflammation can also treat depressive symptoms.74,75 Current research includes identification of biomarkers to help predict response to treatment, development of more rapid-acting pharmacological treatments, and enhancement of brain stimulation techniques as treatment options.76

Diagnosis

An accurate diagnosis is important for delivering the best quality of care. However, depressive disorders can be difficult to diagnose.77 Age, living in a rural setting, and somatic symptoms are a few factors that can contribute to a delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis.77,78 You and your colleagues play an important role in diagnosing and managing patient treatment, especially in a general practice setting.79

The DSM-5 (2013) describes 3 depressive disorders that affect adults.

Major Depressive Disorder

Characterized by a depressed mood for at least 2 weeks. A depressed mood can include decreases in energy, changes in sleep patterns, and feelings of worthlessness or guilt. Other symptoms may include a loss of pleasure or interest in daily activities, frequent hypersomnia or insomnia, fatigue, and difficulty concentrating.20

Persistent Depressive Disorder

Characterized by a depressed mood for most days for 2 years. A depressed mood can include decreases in energy, changes in sleep patterns, and feelings of worthlessness or guilt. Other symptoms may include hypersomnia or insomnia, fatigue, low self-esteem, and difficulty concentrating.20

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

Significant or sudden mood swings, irritability or anger, depressed mood, lethargy, and loss of pleasure or interest in daily activities develop during the week before menses. These symptoms are minimal or absent once monthly menses is complete.20

Depressive symptoms may be secondary to another process or may present differently than the depressive disorders listed above.

- The use of mind-altering substances, some medications, and some medical conditions can cause depressive-like symptoms. In these cases, a diagnosis of substance/medication-induced depressive disorder or depressive disorder due to another medical condition may be given.20

- Depressive symptoms that do not fit the criteria for any of the above disorders may be classified as other specified depressive disorder.20 Sometimes, when no specific diagnosis can be made such as in an emergency department in which pertinent medical information is unavailable, a diagnosis of unspecified depressive disorder may be rendered.20

When considering a depressive disorder diagnosis for your patients, rule out other causes of the presenting symptoms, such as medication or another medical condition. See the end of the Diagnosis section for examples of conditions that can cause depressive-like symptoms.

Signs and Symptoms

Talking to Your Patients

While one of the more common mental disorders, depressive disorders can still be difficult to diagnose. General practitioners misdiagnose depressive disorders, either through a mistaken diagnosis or a missed diagnosis, approximately 25% of the time.80

In large part, this is likely due to how difficult it can be to identify symptoms that are not severe or acute.80 Current diagnostic tools also do not always prioritize those depressive symptoms that are most associated with the correct diagnosis of depressive disorders.81,82

Another part of making an accurate diagnosis is asking the right questions. Patients with bipolar disorder often get misdiagnosed with major depressive disorder.83 For example, in one large study, 31.2% of patients that screened positive for bipolar disorder had previously received a diagnosis of unipolar depression.84 One reason this happens is because patients may not report hypomanic symptoms, as they do not perceive them to be a problem85, or they do not think of them as connected to a mental disorder.86,87 For other examples of disorders that may have similar symptoms to depressive disorders, scroll down to “Differential diagnoses to consider” at the end of this section.

It can be difficult to translate a list of discrete, clinical symptoms to a diagnosis. When assessing a patient, ask about specific symptoms in a way that is approachable. Some ways to do this are:

- Describe symptoms in a way that your patients can relate to in their day-to-day lives. Encouraging detailed responses and being sensitive to different interpretations of severity of symptoms may help with your patients’ understanding and lead to a more complete understanding of symptoms.88,89

- Collect a thorough history, including asking about symptoms of hypomanic, manic, or depressive episodes in close family members to rule out bipolar depression.85 Try to get your patient to think about symptoms that may have happened further back than the last few months.

- Developing a strong relationship with your patient may help to lessen the stigma of a mental disorder diagnosis.90,91 It can also help reduce stress, encourage patients to be involved with their care plan and help increase treatment adherence.91

- Avoid using jargon—using plain language and avoiding technical medical terms will improve your communication with your patient.92 Additionally, using proper terminology may help to lessen the stigma of a mental disorder diagnosis.93,94

Using these methods to communicate the symptoms listed here can be helpful for patient communication and making a diagnosis.

Major Depressive Disorder20

For a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, at least five symptoms must be present most days for 2 weeks or more and one of the symptoms must be depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure in usually enjoyed activities (both symptoms may be present). This mood is accompanied by several additional symptomsa :

- Decrease or increase in appetite, or a ≥5% unintentional increase or decrease in weight over a month

- Insomnia or hypersomnia

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation observable by others

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness, or excessive or inappropriate guilt

- Inability to think, concentrate, or make decisions

- Recurrent thoughts of death, recurrent suicidal ideation, having a specific plan for suicide, or a suicide attempt

Other symptomsa that are associated with major depressive disorder, but cannot be used exclusively for a diagnosis, include20:

- Tearfulness

- Irritability

- Brooding and obsessive rumination

- Anxiety, including excessive worry over physical health

- Phobias

- Pain such as back pain, chest pain, or headaches95

- Nausea95

- Labored breathing95

- Heart palpitations95

- Diarrhea95

- Heavy limbs or a feeling of heavy paralysis96

- Lack of motivation96

- Apathy96

- Decreased muscle strength96

- Difficulty remembering words or events96

- Difficulty maintaining mental focus96

- Sexual dysfunction, including decreased libido and sexual desire, as well as problems with arousal and orgasm97

Persistent Depressive Disorder (Dysthymia)20

For a diagnosis of persistent depressive disorder, or dysthymia, a person has a depressed mood most days for 2 years or more. This mood must be accompanied by at least two additional symptomsa:

- Poor appetite or overeating

- Insomnia or hypersomnia

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Inability to think, concentrate, or make decisions

- Feelings of hopelessness

Other symptoms that are associated with major depressive disorder, but cannot be used exclusively for a diagnosis, include:98

- General feeling of being unwell

- Gloominess

- Pessimism, sarcasm, or nihilism

- A feeling of chronic fatigue

- Low self-confidence

It is possible for a person to have persistent depressive disorder with periods of major depressive disorder.

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder20

Symptomsa are present in the week prior to the majority of menses cycles and improve within a few days of the onset of the menses cycle. These symptoms are minimal or absent once the menses cycle is complete.

At least 1 symptom from each list must be present, and at least 5 symptoms total must be present for a diagnosis.

At least 1 of these symptoms must be present:

- Marked affective lability

- Marked irritability, anger, or increased conflicts

- Marked depression, feelings of hopelessness, or self-deprecating thoughts

- Marked anxiety and/or tension

At least 1 of these symptoms must also be present:

- Decreased interest in activities

- Difficulty concentrating

- Fatigue, lethargy, or lack of energy

- Marked change in appetite, overeating, or specific food cravings

- Hypersomnia or insomnia

- Feeling overwhelmed or out of control

- Physical symptoms (breast tenderness or swelling, joint or muscle pain, feeling bloated, weight gain)

Other symptomsa that are associated with premenstrual dysphoric disorder, but cannot be used exclusively for a diagnosis, include:

- Delusions or hallucinations20

- Thoughts of suicide, suicidal ideation, plans for suicide, or suicide attempt20,99

- Self-doubt100

- Difficulty with social interactions100,101

- Guilt or overcompensation related to presenteeism100

- Impulsivity101

Specifiers

Specifiers are descriptors in the DSM-5 that can be added to a diagnosis of major depressive disorder or persistent depressive disorder, allowing for the description of additional symptomsa or patterns that are not part of the base diagnosis.20 A patient who has a specifier as a part of their diagnosis is not unusual – rather, the specifiers allow for a more nuanced diagnosis and treatment plan.

| Specifier21 | Definition | Can be applied to… |

| Anxious distress | The presence of at least two of the following symptoms for most days:

| The most recent or current major depressive episode or persistent depressive disorder |

| Atypical features | The presence of mood reactivity, when the mood brightens in response to actual or potential positive events, along with at least two of the following symptoms:

| The most recent or current major depressive episode or persistent depressive disorder |

| Three or more of the following symptoms are present for most of the episode:

| The most recent or current major depressive episode or persistent depressive disorder |

| Melancholic features | A loss of pleasure in most activities or experiencing few or no feelings of pleasure when something good happens, along with at least three of the following symptoms:

| The most severe stage of a current major depressive episode or persistent depressive disorder |

| Mixed features | At least three of the following hypomanic or manic symptoms are present:

| The most recent or current major depressive disorder episode |

| Peripartum onset | The onset of the depressive episode happens during pregnancy or in the 4 weeks postpartum. | The most recent or current major depressive episode |

| Psychotic features | The presence of delusions or hallucinations during an episode. | The most recent or current major depressive episode or persistent depressive disorder |

| Seasonal pattern | A long-term pattern of depressive episodes that occur and then subside corresponding with a particular time of year. This must happen for at least 2 years, with no nonseasonal episodes occurring during that same period. | Recurrent major depressive disorder episodes |

aThe symptoms in these definitions are adapted from the DSM-5 (2013) so as to avoid any misinterpretation. Please refer to the DSM-5 (2013) published by the American Psychiatric Association for the full diagnostic criteria.

Diagnostic and Screening Tools

You can use a number of validated scales to assess symptoms related to depressive disorders. While these scales are useful tools, depressive disorders have many types of symptoms. making it important to carefully assess the whole patient prior to making a diagnosis.102,103 A selection of a diagnostic and screening tools can be found here. For additional information about the diagnosis process, scroll down to the Treatment Guidelines section.

Differential Diagnoses to Consider

Depressive disorders have symptoms that overlap with other mental disorders, which can make them difficult to diagnose.20 A careful evaluation of patient symptoms and history is important for proper treatment. The following lists are differential diagnoses that should be considered prior to making a diagnosis of a depressive disorder.Other diagnoses that should be considered prior to making a diagnosis of major depressive disorder or persistent depressive disorder include:

Other Depressive Disorders

Differential diagnoses are made by a careful consideration of the timing and length of the symptoms.20

Depression Due to Substance Use, a Medical Condition, or Medication

Careful examination of patient history, laboratory results and the timing of depressive symptoms in relation to the use of substances or medication can help make an accurate diagnosis.20

Bipolar Disorder

If a person has experienced at least one episode of mania or hypomania at any point in their life, a diagnosis of a depressive disorder is excluded.23 However, mixed symptoms in depressive disorders are a risk factor for the development of bipolar disorder, and patients with this specifier should be monitored for a hypomanic or manic episodes.20

Schizophrenia

Depressive symptoms are a common associated feature of chronic psychotic disorders.23 Identifying the timing of delusions in relationship to mood disorders can aid diagnosis: if delusions only occur during depressive episodes, the diagnosis is more suggestive of depression with psychotic features.20

Personality Disorder

Personality disorders share many characteristics with other mental disorders. A personality disorder should be diagnosed only when the defining characteristics have been present since before early adulthood and are typical of the patient’s long-term behavior. Personality disorders are also persistent and do not occur in an episodic manner.20

Significant Loss

Losses such as bereavement, a serious illness, natural disasters, or financial distress can lead to symptoms similar to depressive disorders. Examining the patient’s history and context for depressive symptoms can help distinguish a major depressive episode from normal grief.20

Other diagnoses that should be considered prior to making a diagnosis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) include:

Premenstrual Syndrome

Premenstrual syndrome is generally considered to be less severe than PMDD and does not require a minimum of 5 symptoms for diagnosis.20

Dysmenorrhea

Dysmenorrhea is characterized by pelvic pain during menstruation, and does not include the affective symptoms prior to menstruation.20,104

Hormonal Treatments

If PMDD symptoms occur after the initiation of hormonal therapy, the symptoms may be due to the use of hormones. Similarly, if cessation of hormonal therapy coincides with a decline in symptoms, the hormonal therapy may be the cause.20

Bipolar Disorder or Other Depressive Disorders

The affective symptoms of PMDD can appear similar to bipolar disorder or other depressive disorders. Menses can also worsen preexisting bipolar and depressive symptoms.105,106 This can make it difficult to distinguish PMDD from bipolar disorder or depressive disorders. PMDD is characterized by symptoms that follow a pattern, starting a few days before the period and resolving shortly after the period starts.20 It may be helpful to have patients chart their symptoms over a period time in order to identify a pattern, especially as retrospective recall of symptoms may be unreliable for an accurate diagnosis of PMDD.20

Hyper- and Hypo-Thyroidism

These diagnoses can be distinguished by symptoms that are not associated with PMDD. For hyperthyroidism, these include weight loss, heat intolerance, disturbances to the heart rhythm, and hyperreflexia. For hypothyroidism, differential symptoms include constipation, cold intolerance, dry skin, and delayed deep tendon reflexes.107 Thyroid tests can also rule out a PMDD diagnosis.108

Anemia

Anemia can be distinguished from PMDD through a complete blood count test.108

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

While symptoms can overlap between both disorders, symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder do not fluctuate with the menstrual cycle and may include heart palpitations and feelings of fear, which are not symptoms of PMDD.107

Menstrual Migraine

PMDD occurs in relation to ovulation and resolves shortly after the start of menstruation, while menstrual migraines can occur throughout menstruation and in the absence of ovulation.109

In addition, endometriosis may produce symptoms similar to PMDD and should be considered.110 It can be differentiated by examining the history of symptoms and making a physical examination.

Psychiatric Comorbidities

Depressive disorders can also be comorbid with other mental and medical conditions, many of which can have similar symptoms.111 It is important that patients receive accurate diagnoses so that they can receive proper treatment.

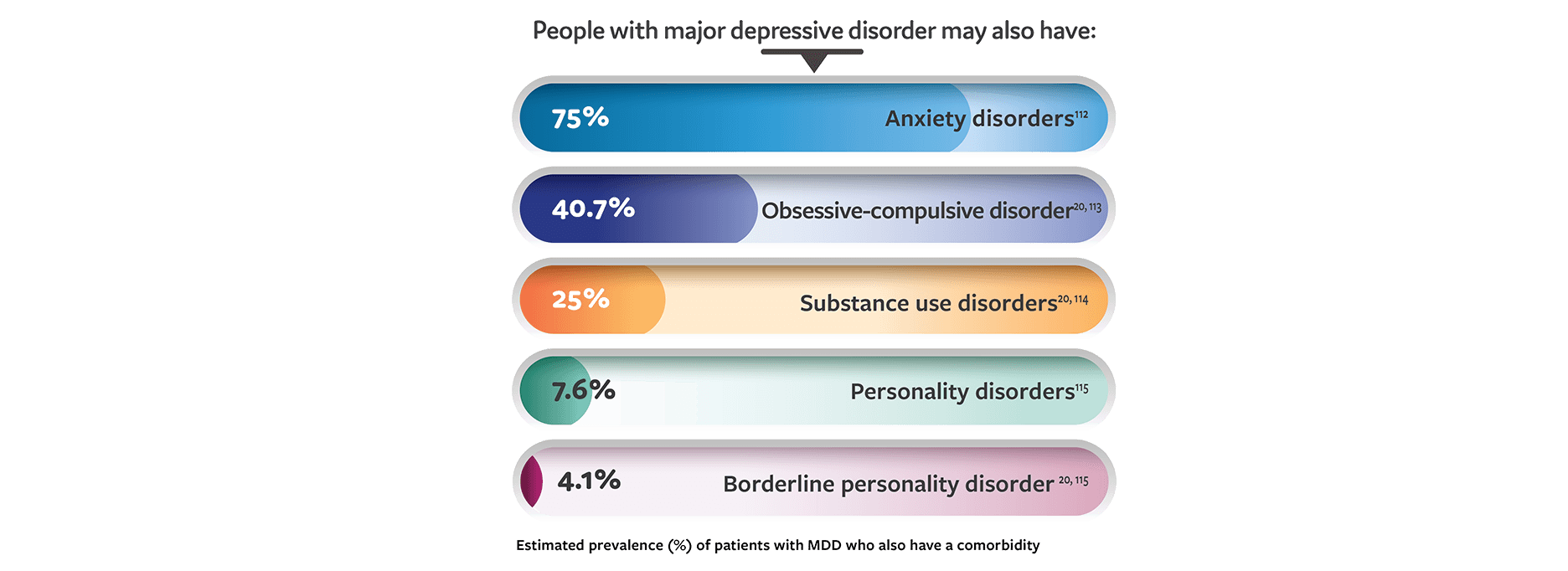

People with major depressive disorder may have additional psychiatric conditions. The estimated prevalence of some additional psychiatric comorbidities in major depressive disorder are as follows: anxiety disorders, 75%; obsessive-compulsive disorder, 40.7%; substance-use disorder, 25%; personality disorders, 7.6%; borderline personality disorder, 4.1%. [20,112-115]

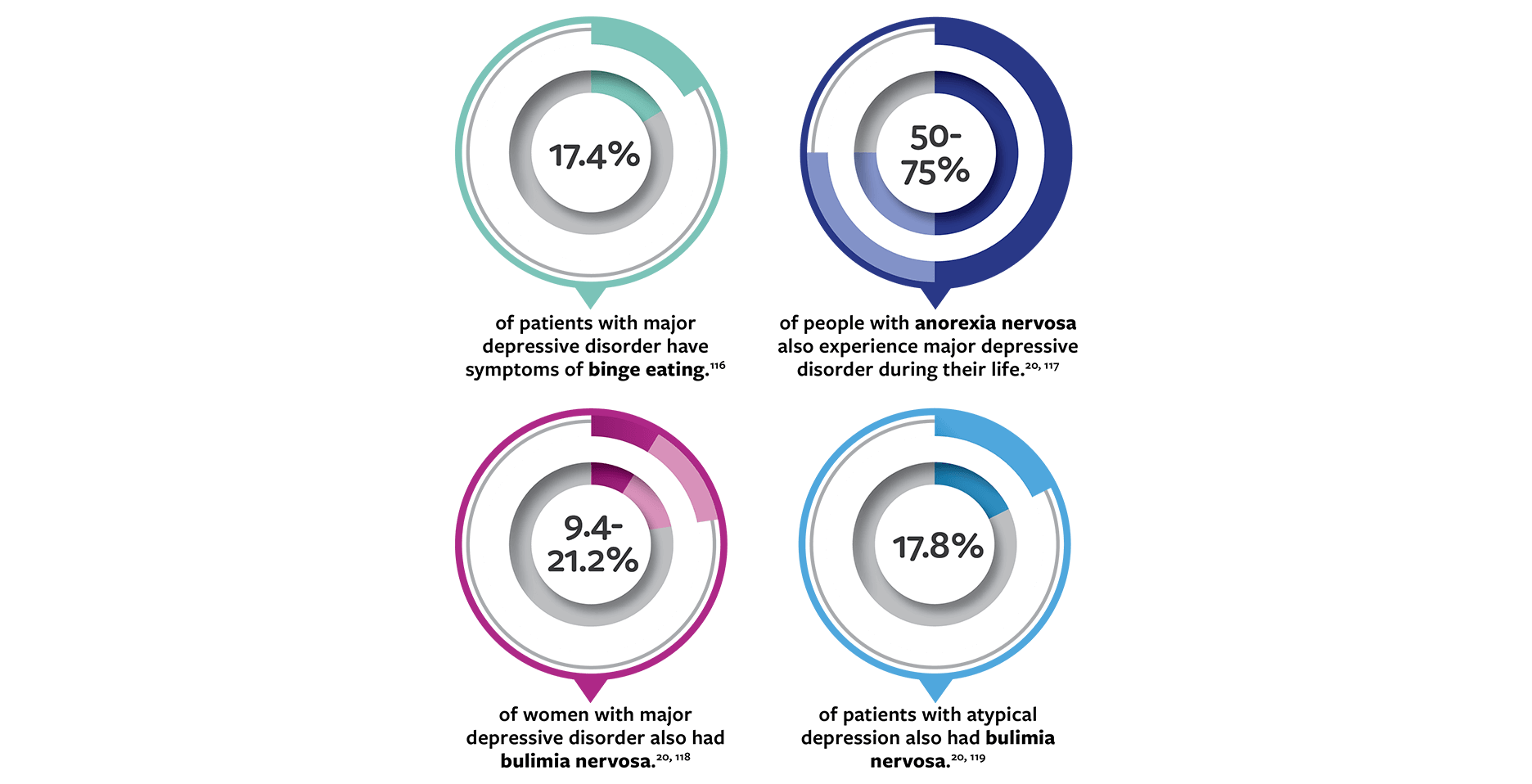

Eating disorders are known to be connected to major depressive disorder, but most research has focused on depressive symptoms in patients with eating disorders, rather than eating disorders in patients with depressive symptoms.

17.4% of patients with major depressive disorder have symptoms of binge eating. [116] Fifty to 75% of people with anorexia also experience major depressive disorder during their life. [20, 117] 9.4% to 21.2% of women with major depressive disorder also had bulimia nervosa. [20, 118] 17.8% of patients with atypical depression also had bulimia nervosa. [119]

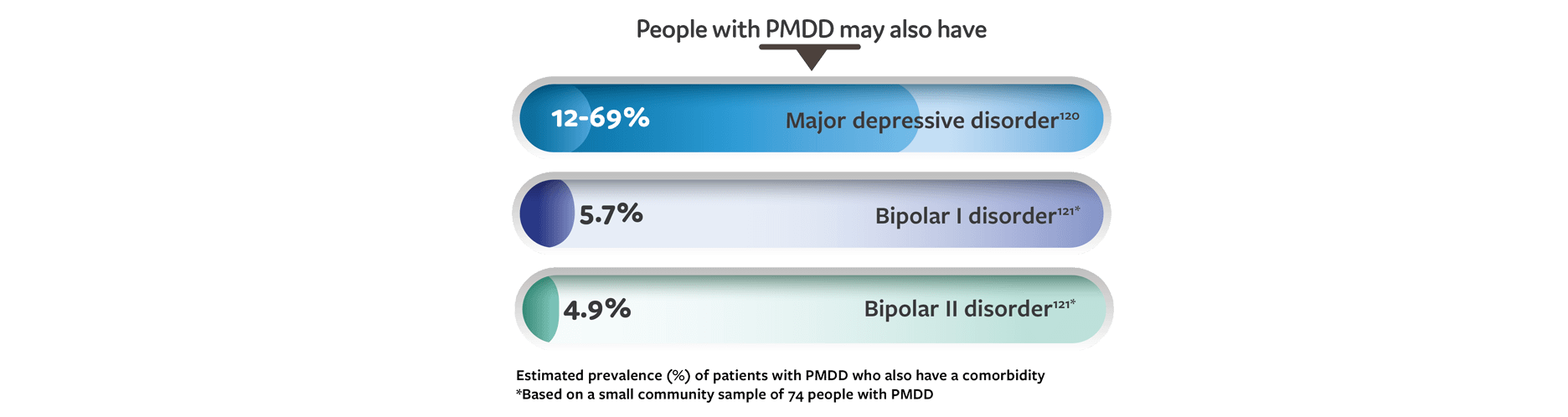

People with PMDD may also have major depressive disorder with an estimated prevalence of 12 to 69%. [120] Another potential comorbidity is bipolar disorder: A small community sample of 74 people with PMDD found that 5.7% also had bipolar I disorder and 4.9% also had bipolar II disorder. [121]

People with PMDD may also have premenstrual exacerbation: While a range of medical and mental disorders may worsen during the premenstrual phase, this exacerbation alone does not qualify as a diagnosis of PMDD. PMDD may increase the symptom severity of preexisting medical or mental disorders in the week prior to menstruation, but also causes additional symptoms that are not present outside the premenstrual period.20,105,119

Distinguishing symptoms of depressive disorders from other mental and physical disorders can be challenging. However, your dedication to finding the right diagnosis will be beneficial to improving your patients’ well-being.

Treatment of MDD

Understanding the Patient Journey: The Importance of Early Treatment

Although patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) are commonly seen in clinical practice, MDD can be challenging for healthcare providers to identify and diagnose.80 Standardized psychiatric rating scales such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) can be helpful in screening, diagnosing, and monitoring the condition.122,123 Delays in diagnosis result in delays in treatment, which can prolong symptoms and lead to negative consequences for the patient in the long term.60

Moreover, as shown in the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial, treatment response and remission rates decrease substantially after initial and next step treatment for MDD, underscoring the importance of accurate initial and ongoing assessment as well as early and adequate treatment of the disease.124

Ultimately, remission is the goal of treatment. Patients who do not achieve remission or who continue to experience residual symptoms are at high risk for relapse or recurrence.125 Regular monitoring of depressive symptoms with standardized psychiatric rating scales, such as the Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (IDS), Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D), and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) can be used to support early detection of recurrent symptoms and assess response to treatment.122

When a diagnosis of MDD is made early and adequate treatment is started soon after the onset of a depressive episode, a patient’s prognosis can significantly improve. With measurement-based follow-up care, functional recovery and remission are the goals of treatment.60

Initial Treatment of MDD

After psychiatric evaluation results in a diagnosis of MDD, it is important to ensure that the patient is not a danger to themselves or others. Healthcare providers must assess for suicidal ideation and homicidal ideation. In any patient judged to be a risk to themselves or others, inpatient psychiatric treatment should be pursued.122

Among patients judged appropriate for outpatient psychiatric care, recommended treatment options include psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy or both.122 For initial treatment, in the context of shared decision-making with the patient, psychotherapy and/or an antidepressant (ADT) medication can be considered.126 First-generation antidepressant medications include monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). Second-generation antidepressants include but are not limited to serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), 5-HT2 receptor antagonists, and dopamine reuptake inhibitors. First-generation antidepressant medications are tolerated less and have increased toxicity in overdose. Second-generation antidepressants are more common in current medical management of depressive disorders as they have a more favorable side-effect profile.127

No antidepressant has been proven more efficacious than another.122 All antidepressant medications that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are deemed appropriate for first-line treatment. Side effect profiles, comorbid conditions, food-drug interactions, drug-drug interactions, and previous medication trials can help guide the provider in considering classes of drugs for each patient.122 A second-generation antidepressant such as an SSRI or an SNRI is often chosen for initial therapy.122

Once an antidepressant medication is started, titration to the therapeutic dose will depend on the patient’s age, the presence of comorbidities, other medicines they take, the patient’s response to the ADT, and potential side effects.122 Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic factors can also affect the optimal dosage required by each patient.122 It is important to review with patients starting antidepressant therapy that these medications may take 2 to 4 weeks before beneficial effects are noticed, and up to 4 to 6 weeks to achieve maximum therapeutic effects.122

Follow-up with the patient after treatment initiation should include reviewing depressive symptoms through the use of clinician- or patient-administered rating scales.122 The PHQ-9 is one of the most commonly used adult depression screening tools and has demonstrated clinical utility and diagnostic accuracy.123 The healthcare provider should follow-up and monitor changes in the PHQ-9 score or other screening tools utilized, to determine that the patient is appropriate for continued outpatient treatment.122

Addressing Inadequate Treatment Response in MDD

While many patients will respond to initial pharmacotherapy, up to 50% of patients do not adequately respond.128,129 There is no standard definition of adequate treatment response in MDD. However, in general, nonresponse is defined as less than 25% improvement from baseline on a standardized depression rating scale.130 Partial response is defined as at least 25% but less than 50% improvement.130 At least 50% reduction in symptomatology indicates adequate response.130 Both treatment nonresponse and partial response are characterized by residual depressive symptoms, which can be associated with continuing disability and increased risk for MDD relapse and recurrence.130

Among patients not showing adequate response to first-line monotherapy, the APA recommends first optimizing the dosage of current pharmacotherapy if tolerability of side effects permits and if the upper limit of a medication dose has not been reached.122

The clinician should also interview the patient for possible contributing factors to inadequate response and assess for treatment adherence.122 Consider the presence of comorbid general medical or psychiatric conditions (eg, substance use disorder) or possible psychosocial or psychological factors that could impede recovery.122

If inadequate treatment response persists over another 4 to 8 weeks, an alternate treatment plan should be considered.122 This can include switching to another antidepressant medication in the same class, switching to an antidepressant medication from another class, combining 2 antidepressant medications, or augmenting the current antidepressant with adjunctive pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy.122 Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is also an effective option for treatment-resistant symptoms after continuous lack of response to pharmacotherapy in a patient’s treatment journey.122

Switching to a new antidepressant may be appropriate if the patient is having difficulty tolerating side effects or has had no response to their current medication. However, clinicians must educate the patient that this strategy can leave the patient untreated until the newly prescribed antidepressant takes effect, which generally occurs weeks after starting it.122,131 There is little evidence that switching to another medication from the same antidepressant class is effective. However, switching to an antidepressant from another class has been shown to be effective (eg, a patient with no response to an SSRI could try an SNRI).132

In patients with partial response to antidepressant therapy, augmenting with medication or psychotherapy may be preferred. The idea is that augmentation therapy can build upon the initial partial response of the antidepressant monotherapy.131

A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis of 115 studies concluded that specific agents showed particular efficacy when used as adjunctive therapies in MDD not responsive to first-line therapies.128 Atypical antipsychotics, atypical antidepressants, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) were among the treatments shown to be effective as adjunctive therapies to antidepressants.128 Of these, only atypical antipsychotics are FDA-approved as adjunctive pharmacotherapies for patients with MDD and partial response to initial therapy.

The use of atypical antipsychotic medications as adjunctive therapy to antidepressants has been an area of focus for many years and continues to be a widely recognized and successful treatment option.133 There are currently 4 atypical antipsychotics with FDA approval for adjunctive treatment of MDD.

The American Psychological Association recommends the following forms of psychotherapy as adjunct treatment in patients with partial response to pharmacologic monotherapy126:

- interpersonal psychotherapy

- CBT

- psychodynamic psychotherapy

Creating alternate treatment pathways can be a complex process and should include shared decision-making with the patient.

Non-Pharmacological Management for MDD

Patients can follow non-pharmacological approaches to treatment that can help with managing MDD, some of which are listed below. By educating your patients about these additional treatment options, you can help them feel more in control of their mental health.

Psychotherapy

Research shows that psychotherapy in conjunction with medication may reduce symptoms of MDD and enhance well-being.134,122 Many types of psychotherapy have been shown to have similar benefits126:

- CBT

- Behavioral therapy/behavioral activation

- Psychodynamic therapy

- Problem-solving therapy

- Interpersonal therapy

- Mindfulness-based therapy

Help guide your patients in determining their preferences and treatment goals to choose the psychotherapy style and practitioner that fit them best.126

Neuromodulation

For patients who do not respond to multiple trials of pharmacotherapy for MDD, neurostimulation treatment can be considered.135 ECT,136 vagus nerve stimulation (VNS),137 deep brain stimulation (DBS),138 and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS)139 have all been used.

Complementary and Alternative Treatments

The American Psychological Association lists bright light therapy, yoga, and acupuncture as conditionally recommended complementary therapies for MDD. These therapies, along with St. John’s Wort monotherapy and exercise monotherapy, are listed as conditionally recommended alternative therapies for MDD for patients for whom pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy is either ineffective or unacceptable.126

Lifestyle Modifications for MDD

While taking medications is often the first step in treating MDD, medication can take time to start showing potential effects, and it can take time to find the right medication.122 Your patients can make additional changes that may help manage their MDD. Research studies indicate there may be an association between positive lifestyle modifications and a potential reduction of depressive symptoms. However, the reasons for which they are beneficial for some people with MDD but not others remain unclear. Discussing these lifestyle modifications with your patients, along with ways in which they can make these changes, can help them make the right choices for their individual needs.

Exercise

Obesity is associated with increased rates of clinical depression, and vice versa.140 Exercise is recommended as a complementary treatment to help in treating MDD.126 The American Psychiatric Association recommends that healthcare practitioners provide comprehensive patient education, including encouraging healthy behaviors such as exercise and proper nutrition.122

Healthy Diet

Reduced consumption of saturated fats, refined and added sugars, fried foods, and processed meats is associated with a reduced risk for MDD. Maintaining a diet of whole and fiber-rich foods (including the Mediterranean diet) may help protect against MDD.141

Sleep Hygiene

Insomnia and MDD are frequently experienced as comorbid conditions.142 Poor sleep quality may enhance vulnerability to MDD.143 Improving sleep in depressed patients is associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms.144

Mindfulness

Some research has indicated that mindfulness practices such as meditation can help with mood symptoms and insomnia. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy is sometimes used to delay or prevent recurrence of major depression.145

Substance Use

Nicotine use and MDD share substantial comorbidity. Daily smoking has been associated with an increased risk of developing MDD in longitudinal studies.146 One study noted a fourfold increase in depression among heavy smokers as compared to those who never smoke.147 It is important to note that this relationship is not known to be causative, however significant it may seem. Quitting smoking may be beneficial for your physical health in many ways.148

Similarly, alcohol use disorders and MDD also co-occur frequently among patients.149 There is evidence to support each of the following: depressive disorders increase risk for alcohol use disorders, alcohol use disorders increase the risk for depressive disorders, and finally, both alcohol use disorders and MDD share common pathophysiological origins and risk factors.149

References

Karpov, B et al. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;44:83-89.

- Rizvi, SJ et al. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(1):14-22.

- Forehand, R et al. J Fam Psychol. 2012;26(4):532-541.

- Wilson, S & Durbin, CE. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(2):167-180.

- Stickley, A et al. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):12011.

- Gibson-Smith, D et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;106:1-7.

- Husain, MM et al. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13(10):852-860.

- Fulkerson, JA et al. Prev Med. 2004;38(6):865-875.

- Schuch, F et al. J Affect Disord. 2017;210:139-150.

- Vancampfort, D et al. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):308-315.

- Cipriani, A et al. The Lancet. 2018;391(10128):1357-1366.

- Schefft, C et al. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;139(4):322-335.

- Barth, J et al. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001454.

- Backs-Dermott, BJ et al. J Affect Disord. 2010;124(1-2):60-67.

- Barger, SD et al. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:273.

- Shimazu, K et al. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(5):385-390.

- Zilcha-Mano, S et al. J Affect Disord. 2014;152-154:538-542.

- Ridge, D & Ziebland, S. Qual Health Res. 2006;16(8):1038-1053.

- Nunstedt, H et al. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33(5):272-279.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edn (2014).

- Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. (World Health Organization, 2017).

- Kessler, RC et al. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21(3):169-184.

- Otte, C et al. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16065.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, CfBHSaQ. Mental Health Annual Report: 2017. Use of Mental Health Services: National Client-Level Data. 2019. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Rockville, MD.

- Major Depression. Mental Health Information: Statistics. 2019. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- Greer, TL et al. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(4):267-284.

- Rock, PL et al. Psychol Med. 2014;44(10):2029-2040.

- Listunova, L et al. Psychopathology. 2018;51(5):295-305.

- Kessler, RC et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1561-1568.

- Kupferberg, A et al. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;69:313-332.

- Siddiqui, S & Khalid, J. Pak J Med Sci. 2019;35(5):1329-1333.

- Zivin, K et al. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36(4):631-649.

- Lang, UE et al. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;37(3):1029-1043.

- Kiecolt-Glaser, JK et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(11):1075-1091.

- Hare, DL et al. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(21):1365-1372.

- Serpytis, P et al. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2018;111(5):676-683.

- Li, L et al. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):375.

- MacQueen, GM & Memedovich, KA. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;71(1):18-27.

- de Beurs, D et al. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):345.

- Dong, M et al. Psychol Med. 2019;49(10):1691-1704.

- Olfson, M et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(11):1095-1103.

- Lam, RW et al. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):510-523.

- Savard, M. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;6(Suppl 1):17-24.

- American Psychiatric Association. What is Depression? 2017. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/depression/what-is-depression. Accessed February 14, 2020.

- Brown, C et al. Fam Pract. 2001;18(3):314-320.

- Naushad, N et al. J Affect Disord. 2018;229:456-462.

- Alderson, SL et al. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:41.

- Alderson, SL et al. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:37.

- Barney, LJ et al. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:88.

- Fernandez-Pujals, AM et al. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142197.

- Hyde, CL et al. Nat Genet. 2016;48(9):1031-1036.

- Kendler, KS et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):109-114.

- Kotov, R et al. Psychol Bull. 2010;136(5):768-821.

- Lubke, GH et al. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(8):707-709.

- Okbay, A et al. Nat Genet. 2016;48(6):624-633.

- Smith, DJ et al. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(6):749-757.

- Sullivan, PF et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(10):1552-1562.

- Menard, C et al. Neuroscience. 2016;321:138-162.

- Levy, MJF et al. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(8):2195-2220.

- Oluboka OJ, Katzman MA, Habert J, et al. Functional recovery in major depressive disorder: providing early optimal treatment for the individual patient. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;21(2):128-144.

- Newman, SC & Bland, RC. Compr Psychiatry. 1994;35(1):76-82.

- Hettema, JM et al. Psychol Med. 2006;36(6):789-795.

- Risch, N et al. JAMA. 2009;301(23):2462-2471.

- Wang, J et al. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(1):52-59.

- Goodyer, IM et al. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:499-504.

- Harris, TO et al. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:505-510.

- Vreeburg, SA et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(6):617-626.

- Fardet, L et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):491-497.

- Paragliola, RM et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(10).

- Kingsbury, M et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(8):709-716 e702.

- Murphy, SK et al. Psychiatry Res. 2017;257:102-110.

- Gavin, NI et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5 Pt 1):1071-1083.

- van Zoonen, K et al. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):318-329.

- Rapaport, MH et al. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(1):71-79.

- Raison, CL et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(1):31-41.

- Kraus, C et al. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):127.

- Ghesquiere, AR et al. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(11):1471-1476.

- Shetty, P et al. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60(1):97-102.

- Keller, AO et al. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2018;45(2):310-319.

- Mitchell AJ, Vaze A, Rao S. Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;374(9690):609-619. 80

- Olivan-Blazquez, B et al. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2016;44(2):55-63.

- Fried, EI et al. J Affect Disord. 2016;189:314-320.

- Kriebel-Gasparro, AM. Open Nurs J. 2016;10:59-72.

- Hirschfeld, RM et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(1):53-59.

- Koirala, P & Anand, A. Cleve Clin J Med. 2018;85(8):601-608.

- Regeer, EJ et al. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):22.

- Liu, X & Jiang, K. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2016;28(6):343-345.

- Yeung, A & Kam, R. Transcult Psychiatry. 2008;45(4):531-552.

- Unutzer, J & Park, M. Prim Care. 2012;39(2):415-431.

- Mestdagh, A & Hansen, B. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(1):79-87.

- Dang, BN et al. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):32.

- Hersh, L et al. Am Fam Physician. 2015;92(2):118-124.

- Broyles, LM et al. Subst Abus. 2014;35(3):217-221.

- Thom, R & Farrell, H. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(3):253-259.

- Sato, S & Yeh, TL. CNS Drugs. 2013;27 Suppl 1:S5-10.

- Zajecka, J et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(4):407-414.

- Maru, RK et al. Open Journal of Psychiatry & Allied Sciences. 2019;10(1):26.

- Melrose, S. Open Journal of Depression. 2017;06(01):1-13.

- Ducasse, D et al. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148653.

- Hardy, C & Hardie, J. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;38(4):292-300.

- Petersen, N et al. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19(5):891-898.

- Dipnall, JF et al. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0167055.

- Flux, MC & Lowry, CA. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;135:104578.

- Bernardi, M et al. F1000Res. 2017;6:1645.

- Eisenlohr-Moul, TA. The Clinical Psychologist. 2019;72(1):5-17.

- Dias, RS et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(4):386-394.

- Mishra, S & Marwaha, R. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder in StatPearls [Internet] (StatPearls Publishing, 2019).

- Casper, R. Patient education: Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) (Beyond the Basics) in UpToDate (eds PJ Snyder & WF Crowley) (UpToDate, 2019).

- MacGregor, EA. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21(3):309-315.

- Hofmeister, S & Bodden, S. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(3):236-240.

- Lamers, F et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):341-348.

- Ruscio, AM et al. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(1):53-63.

- Hunt, GE et al. J Affect Disord. 2020;266:288-304.

- Angstman, KB et al. J Prim Care Community Health. 2017;8(4):233-238.

- Baek, JH et al. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198192.

- Thornton, LM et al. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2016;46(5):525-534.

- Wildes, JE et al. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38(1):9-17.

- Perugi, G et al. J Affect Disord. 2006;92(1):91-97.

- Kim, D & Freeman, E. Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder and Psychiatric Comorbidity. Psychiatric Times. 2010. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/comorbidity-psychiatry/premenstrual-dysphoric-disorder-and-psychiatric-comorbidity. Accessed February 28, 2020.

- Cirillo, PC et al. Braz J Psychiatry. 2012;34(4):467-479.

- Cheung, AH et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3).

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (3rd edition). . 2010. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/clinical-practice-guidelines. Accessed June 22, 2020.

- Siniscalchi KA, Broome ME, Fish J, et al. Depression screening and measurement-based care in primary care. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720931261.

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905-1917.

- Judd LL, Paulus MJ, Schettler PJ, et al. Does incomplete recovery from first lifetime major depressive episode herald a chronic course of illness? Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1501-1504.

- American Psychological Association. APA clinical practice guideline for the treatment of depression across three age cohorts.2019. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://www.apa.org/depression-guideline/guideline.pdf

- O'Connor EA, Whitlock EP, Gaynes B, Beil TL. Screening for Depression in Adults and Older Adults in Primary Care: An Updated Systematic Review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2009.

- Scott F, Hampsey E, Gnanapragasam S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of augmentation and combination treatments for early-stage treatment-resistant depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2022;2698811221104058.

- Rafeyan R, Papakostas GI, Jackson WC, Trivedi MH. Inadequate response to treatment in major depressive disorder: augmentation and adjunctive strategies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3):OT19037BR3.

- Nierenberg AA, DeCecco LM. Definitions of antidepressant treatment response, remission, nonresponse, partial response, and other relevant outcomes: a focus on treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62. Suppl 16:5-9.

- Kurian BT, Greer TL, Trivedi MH. Strategies to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of antidepressants: targeting residual symptoms. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9(7):975-984.

- Voineskos D, Daskalakis ZJ, Blumberger DM. Management of treatment-resistant depression: challenges and strategies. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:221-234.

- Wang SM, Han C, Lee SJ, et al. Second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of major depressive disorder: an update [published correction appears in Chonnam Med J. 2019;55(1):73]. Chonnam Med J. 2016;52(3):159-172.

- Cleare A, Pariante CM, Young, AH, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2008 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2015;29(5):459-525.

- O'Reardon JP, Cristancho P, Peshek AD. Vagus nerve stimulation (vns) and treatment of depression: to the brainstem and beyond. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2006;3(5):54-63.

- Kellner CH, Greenberg RM, Murrough JW, Bryson EO, Briggs MC, Pasculli RM. ECT in treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(12):1238-1244.

- Young AH, Juruena MF, De Zwaef R, Demyttenaere K. Vagus nerve stimulation as adjunctive therapy in patients with difficult-to-treat depression (RESTORE-LIFE): study protocol design and rationale of a real-world post-market study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):471.

- Hitti FL, Yang AI, Cristancho MA, Baltuch GH. Deep brain stimulation is effective for treatment-resistant depression: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9):2796.

- Vogel J, Soti V. How far has repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation come along in treating patients with treatment-resistant depression? Cureus. 2022;14(6):e25928.

- Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):220-229.

- Gangwisch JE, Hale L, Garcia L, et al. High glycemic index diet as a risk factor for depression: analyses from the Women's Health Initiative. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102(2):454-463.

- Carney CE, Edinger JD, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Cognitive behavioral insomnia therapy for those with insomnia and depression: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Sleep. 2017;40(4):zsx019.

- Franzen PL, Buysse DJ, Rabinovitz M, Pollock BG, Lotrich FE. Poor sleep quality predicts onset of either major depression or subsyndromal depression with irritability during interferon-alpha treatment. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177(1-2):240-245.

- Murphy MJ, Peterson MJ. Sleep disturbances in depression. Sleep Med Clin. 2015;10(1):17-23.

- Segal ZV, Kennedy S, Gemar M, Hood K, Pedersen R, Buis T. Cognitive reactivity to sad mood provocation and the prediction of depressive relapse. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(7):749-755.

- Bakhshaie J, Zvolensky MJ, Goodwin RD. Cigarette smoking and the onset and persistence of depression among adults in the United States: 1994-2005. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;60:142-148.

- Klungsøyr O, Nygård JF, Sørensen T, Sandanger I. Cigarette smoking and incidence of first depressive episode: an 11-year, population-based follow-up study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(5):421-432.

- United States Public Health Service Office of the Surgeon General; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. Smoking cessation: a report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020.

- McHugh RK, Weiss RD. Alcohol use disorder and depressive disorders. Alcohol Res. 2019;40(1):arcr.v40.1.01.

This resource is intended for educational purposes only and is intended for US healthcare professionals. Healthcare professionals should use independent medical judgment. All decisions regarding patient care must be handled by a healthcare professional and be made based on the unique needs of each patient.

ABBV-US-00386-MC, Version 1.0

Approved 01/2024

AbbVie Medical Affairs

Additional Resources about Major Depressive Disorder

Clinical Article

Anhedonia and Cognitive Function in Adults With MDD: Results From the International Mood Disorders Collaborative Project

The International Mood Disorders Collaborative Project found a significant correlation between anhedonia and self-reported cognitive impairment in adults with major depressive disorder (MDD), which may help to identify individuals with MDD who are at higher risk of cognitive decline over time.

Clinical Article

Unrecognized Bipolar Disorder in Patients With Depression Managed in Primary Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Daveney et al explore the characteristics of patients with mixed symptoms, as compared to those without mixed symptoms, in both bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder.